Key findings

- Birds disturbed regularly flushed to greater distances than birds disturbed less, and this was particularly noticeable in spring and winter.

- Disturbance had no effect on dispersal distances of yearling males and females.

- Disturbed hens laid eggs five days earlier than non-disturbed hens.

Black grouse declined both in range and abundance during the whole of the 20th century. Now they are found only on moorland margins in northern England, where almost 90% are confined to the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. There are areas that have been opened up for increased public access, so the black grouse may be at risk from increased human disturbance.

We undertook a two-year study funded by English Nature to quantify the risk of increased human disturbance on black grouse in northern England. To do this, Mike Richardson and others caught and radio-tagged 77 black grouse between 2002 and 2004 and randomly assigned one of three 'disturbance categories' to each. We disturbed the birds by approaching them until they flushed. We varied the frequency of disturbance from no disturbance (low), weekly disturbance (moderate) to twice weekly disturbance (high). We compared the behaviour (flushing distances, home range size, timing of dispersal, dispersal distances, and the on-set of breeding) and demographic changes (clutch size, breeding success and survival rates) for birds within each disturbance category.

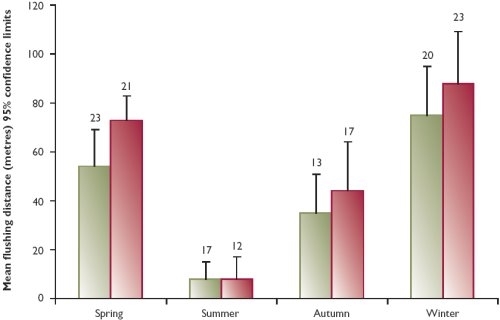

When birds were disturbed regularly, they flushed at greater distances from the observer. This was most noticeable in spring and winter when they flushed at an average of 62 metres and 82 metres (see Figure 1). In this period, birds exposed to a lot of disturbance flushed at 32% greater distances than those subjected to moderate disturbance. For 26 yearling birds, we measured dispersal distances from hatch sites to where they eventually settled and bred. Females dispersed further (6.0 km) than males (0.6 km). Two phases of dispersal occurred in yearling females, the first in late autumn (median date 13 November) and the second in spring (median date 10 April). This was not affected by disturbance. Disturbance influenced the start of breeding, with disturbed females laying on average five days earlier, irrespective of female age or year.

Figure 1: The effects of season and disturbance treatment on flushing distances of black grouse in the North Pennines (sample sizes are given at the top of each column)

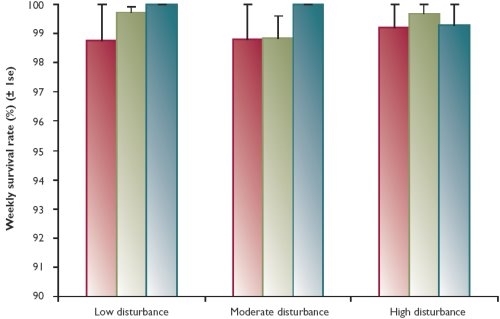

Despite the behavioural differences associated with disturbance, there were no detectable demographic responses, ie. no significant differences in clutch size, hatching success, breeding success or survival between different disturbance treatments. Adult females laid larger clutches (mean 9.3 eggs) than first breeding females (7.4 eggs) and bred more successfully with 51% rearing broods compared with only 13% of juvenile females. Over winter, the weekly survival rates (see Figure 2) were equivalent to 68% of juveniles surviving from September to April, and to 81% of adults. Over summer, they corresponded to a 97% survival of black grouse from May to August. The primary cause of death was predation, chiefly by mammals (65%), with stoats and foxes the main predators, but also raptors (18%).

Figure 2: Weekly survival rates (± 1 se) of black grouse in relation to age, season and disturbance treatment. Juvenile and winter rates are for the period September to April (by which time juveniles have become adult), summer rates are for the period May to August

Although the disturbance regimes in this study did not affect black grouse demography, we cannot be certain that the disturbance levels in our study will be typical of 'open access'. Consequently, the behavioural changes that we observed may have repercussions that we don't know about, so we suggest the following:

- Identifying key wintering sites where birds may be most prone to disturbance and consider restricting access to them.

- Widening the restrictions on dogs to include August and key breeding sites on allotment ground.

- Providing viewing facilities at leks for bird-watchers.

- Monitoring black grouse numbers and habitat use in relation to visitor pressure after access has been opened.