Key findings

- Vaccination of sheep to control ticks reduces incidence of louping ill in red grouse.

- It is possible to suppress louping ill to levels where the impact on red grouse is kept low.

Louping ill is a viral disease transmitted by sheep ticks (Ixodes ricinus) and has been recorded for more than 200 years in Britain in sheep flocks. A recent study showed that it first made its appearance in the UK about 800 years ago. However, its introduction to the heather uplands was probably as late as the 19th century as sheep farming expanded. For this reason red grouse may have only recently come into contact with the virus.

Louping ill is mainly a disease of sheep, although other domestic animals such as cattle, horses, pigs, goats and dogs can also be affected, as can red grouse. In red grouse the virus is responsible for high levels of mortality, with 79% of infected grouse chicks dying from the virus in laboratory and field conditions. It can also cause severe and potentially fatal encephalitis (swelling of the brain) in humans. It is because of its impact on red grouse chick survival that we have been working on control of louping ill since the late 1970s.

In 2001 we reported on the success of treating the major tick hosts (sheep) with acaricides (tick-killing pesticides). Some English estates have adopted this treatment along with vaccination to reduce the prevalence of louping ill in their sheep flocks. A vaccinated sheep produces antibodies which 'kill off' the virus, thus reducing the likelihood of the sheep passing the virus on via the tick to grouse. The vaccination is a split dose with two inoculations a minimum of two weeks apart administered before the sheep return to the moor as one-year-old animals. We have demonstrated that as the maternal antibodies wane in late summer, unvaccinated lambs can amplify and spread the virus. To prevent this, replacement ewe lambs should receive their first vaccination at shearing in July and the second at any time before they return to the moor in the spring.

To test the effectiveness of this sheep vaccination programme on the prevalence of louping ill in red grouse, we collected blood samples from immature red grouse on shoot days. Adult birds do not necessarily reflect louping ill prevalence in the year of sampling, so we do not sample them. From the blood samples we collect, we extract the clear serum, which contains the viral antibodies. However, as louping ill causes 79% mortality in red grouse, most of the birds that have come into contact with the virus will have already died by the start of the shooting season.

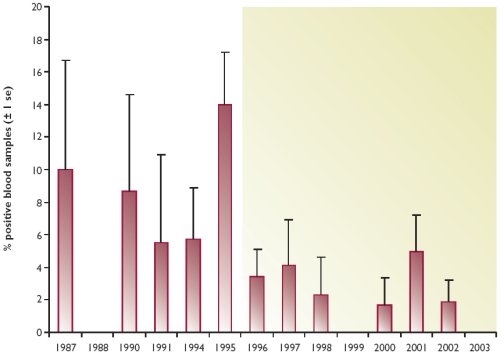

We measured the level of louping ill infection in red grouse on 10 estates in the North York Moors, with a range of vaccination programmes on their sheep flocks. Louping ill prevalence dropped from an average of 9.8% positive samples before 1995 to an average of 2.2% since 1995 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Louping ill prevalence in blood samples of young red grouse shot on 10 estates in the North York Moors

Although louping ill has not been eradicated, the number of positive blood samples has decreased following the implementation of the double vaccination programme since 1995 - with no positive samples in 1999 and 2003. However, tick numbers were also reduced with acaricide and the reduction in louping ill antibodies in red grouse may also be due to reduced tick numbers.

With correct application of these techniques it is possible to suppress louping ill and sheep ticks to levels where their impact on the red grouse population is reduced to a minimum.