Key points

- Tagging is a very important technique for studying many aspects of wildlife biology and is widely used.

- It is important to monitor any effect that the tagging process has on the animal.

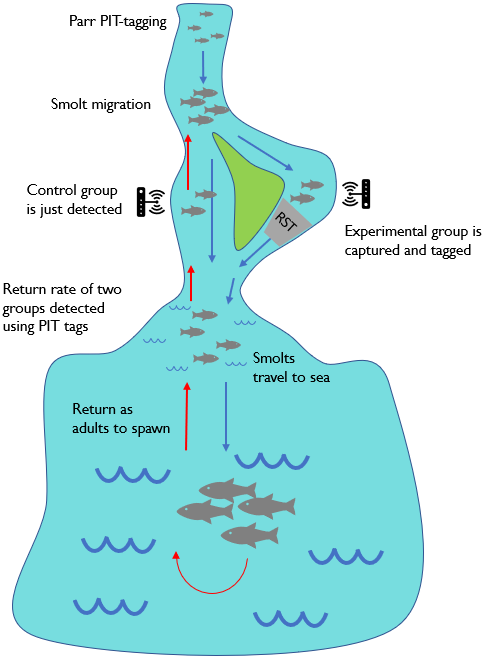

- This study compared two groups of juvenile salmon (smolts): an ‘experimental’ group that were captured and tagged during their spring migration to sea, and a ‘control’ group that were not. It compared the number recorded returning as adults in each group, to see if the capture and tagging process affected their return rate.

- River conditions before, during and after tagging were monitored, including water flow and temperature.

- Capture and tagging of smolts affected the rate at which adults returned only under certain conditions. Those that were caught and tagged during the night and after unusually mild winters, when river temperatures were higher, had a lower chance of returning as adults.

- Knowing about the possible effects of capture and tagging will allow users to adapt their protocols according to the conditions, which should minimise their impacts on the population.

- GWCT Fisheries still capture but no longer tags salmon smolt when they are migrating in spring.

Background

Marking or tagging individual animals is a very important technique for studying many aspects of wildlife biology, including migrations, survival, population changes and behaviour. To give accurate information about its natural behaviour, neither the tag, nor the tagging process should affect the animal.

For salmon, tagging involves catching the fish, giving it a light anaesthetic, and inserting a small tag, before allowing it to recover prior to release. As salmon migrations are affected by environmental conditions, it is also possible that the conditions at the time of tagging could influence whether or not the capture and tagging process affects the fish.

Several different kinds of tags are used to mark salmon, including passive integrated transponders (PIT tags) and coded wire tags (CWT tags).

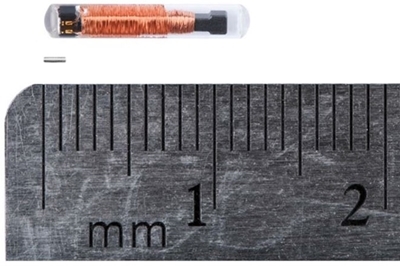

Composite image showing the relative sizes of a PIT tag (top) and CWT tag (bottom).

Composite image showing the relative sizes of a PIT tag (top) and CWT tag (bottom).

PIT tags are used as an individual marker for young fish, they are around 1cm long and 2mm wide. PIT tags have been studied extensively and do not seem to have any adverse effect on fish. The GWCT has, in collaboration with Cefas, PIT-tagged around 10,000 juvenile salmon in the River Frome catchment every autumn since 2005. These PIT-tagged individuals can then be detected as the fish swim past monitoring stations, identifying the individual and letting the scientists know when they are moving up and down the river.

CWT tags are small pieces of magnetised steel, typically 0.25mm wide and 1.1mm long. They have coded numbers engraved onto them, which correspond to the information logged in a database when the fish is tagged. They are detected by a handheld or tunnel detector that can register the presence of a tagged fish, but not the individual tag number. That information is collected when the fish dies and the tag is retrieved. CWT tags were used by GWCT Fisheries to mark seaward migrating smolts between 2006 and 2012, in line with international standards.

What they did

All fish in this study were PIT-tagged in autumn. The scientists then recaptured and CWT-tagged some of the PIT-tagged individuals as migrating smolts in spring. They looked at whether the recaptured individuals had the same adult return rate as smolts that weren’t recaptured in the spring, and whether this was affected by the circumstances under which the secondary tagging took place.

For seven years, the scientists collected data on PIT-tagged fish in two groups:

- Those that were captured in a rotary screw trap and CWT-tagged when migrating to sea as smolts – the ‘experimental’ group.

- Those that were detected migrating to sea as smolts via their PIT tag, but were not captured and CWT-tagged – the ‘control’ group.

The PIT tags were then used to monitor fish returning to their home river as adults to spawn, and this return rate was compared between the two groups. The environmental and river conditions before and at the time of capture and CWT tagging were recorded and included in the analysis, including river temperature and discharge (amount of water flowing).

Experimental group fish were captured using a rotary screw trap. A rotary screw trap is a commonly used floating device that consists of a large conical chamber with a screw thread inside, rotated by the river flow. This traps fish in water pockets and moves them through to a holding chamber, where they can be removed with a net. Captured experimental group fish were then anaesthetised, CWT-tagged, allowed to recover and released within an hour, 50m downstream. The effect of the tagging process cannot be separated out, so any differences between the groups could have been caused by capture, anaesthetic, or tagging, and we cannot determine which part of the process was responsible.

Statistical models were developed to compare the adult return rates of experimental and control group smolts and measure any impact of capture and CWT-tagging. These analyses also accounted for environmental conditions before and during the tagging process.

Table 1: Numbers of Salmo salar parr marked with individual passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags

each autumn; PIT-tagged smolts detected (control group) each spring; PIT-tagged smolts intercepted by

rotary screw trap and tagged with coded-wire tags (experimental group) each spring.

| |

|

PIT-tagged smolts |

|

| Year parr/smolt |

PIT-tagged parr (n) |

Control |

Experimental |

Smolt run PIT tagged (%) |

| 2005/06 |

11,494 |

969 |

325 |

17.4 |

| 2006/07 |

10,882 |

693 |

604 |

10.8 |

| 2007/08 |

10,712 |

718 |

402 |

10.8 |

| 2008/09 |

10,031 |

621 |

447 |

11.3 |

| 2009/10 |

10,835 |

557 |

363 |

7.9 |

| 2010/11 |

10,496 |

476 |

247 |

8.1 |

| 2011/12 |

5,851 |

210 |

244 |

9.1 |

| Totals |

70,301 |

4,244 |

2,632 |

Mean c. 10.8 |

What they found

In years that followed a mild winter, fish in the experimental group that migrated at night had a lower return rate than the control group. This means that fewer smolts from the experimental group returned to their home river as adults. In years with more normal weather conditions and river temperatures, the adult return rate was the same for both groups, suggesting that the extra tag, capture and the process of adding it did not affect the fish.

What does this mean?

After winters with unusually mild river temperatures, the return rate for the experimental group was lower than for the control group, if the smolts travelled at night. This could be because if conditions are not ideal, the smolts are more susceptible to any additional negative effects of capture and CWT-tagging. There are many possible reasons for these findings, for example fish that have undergone the tagging process might be more vulnerable to predation, but there are certainly lots of other factors that are likely to contribute to the chance of adults returning to their home river to breed.

At East Stoke, we still capture a proportion of the spring smolts but CWT-tagging is no longer used. However, these results could help guide all users to minimise their potential impact by being cautious when tagging under these conditions.

Read the original abstract

Riley, W.D., Ibbotson, A.T., Gregory, S.D., Russell, I.C., Lauridsen, R.B., Beaumont, W.R.C., Cook, A.C., & Maxwell, D.L. (2018). Under what circumstances does the capture and tagging of wild Atlantic salmon Salmo salar smolts affect probability of return as adults? Journal of Fish Biology, 93: 477-489.

What do we do?

- We use science to promote game and wildlife management as an essential part of nature conservation.

- We develop scientifically researched game and wildlife management techniques.

- We promote our work to conservationists, including farmers and landowners and offer an on-site advisory service on all aspects of game and wildlife management, so that Britain’s countryside and its wildlife are enhanced for the public benefit.

- We influence government policy with sound science that creates progressive and effective policies.

- We support best practice for field sports that contribute to improving the biodiversity of the countryside.

Donate by Credit or Debit Card >>

Got a PayPal account? Donate faster here:

What do we believe?

- Scientific research should underpin sustainable conservation practice.

- Game and wildlife management is the foundation of good conservation.

- Field sports (in particular shooting and fishing) can contribute substantially to the conservation of landscape, habitat and wildlife.

- Humane and targeted predator control is an essential part of effective game and wildlife conservation.

- We utterly oppose those who engage in wildlife crime.

- Good conservation goes hand-in-hand with economic land use.

How your money is spent

- We spent over £5m on vital game and wildlife research and public education in 2017.

Donate by Credit or Debit Card >>

Got a PayPal account? Donate faster here: