By John Holland, Head of the Farmland Ecology Unit

This is a common question and so here’s an update based upon recent research. First of all though here’s a little bee ecology that may help explain why we need certain types of flowers.

Bee ecology

Pollination is carried out by many different types of insects, although it is widely recognised that bumblebees are the most effective individually because they have hairy bodies that collect lots of pollen, rather like beards! and they can fly at lower temperatures than honeybees, having the ability to warm themselves up in the morning. However, there are only 24 species of bumblebee with six being common whilst there are 225 species of non-social bee, usually called solitary bees, so they are also important in the pollination of crops and wild plants.

Bumblebees vary in tongue length (short to long tongued) and this determines which flowers they are able to collect nectar from. Only long tongued bees can collect nectar from flowers with deep corollas, such as legumes (Fabaceae) and these are the bumblebees that have declined most. Solitary bees have short tongues and can be more specialised, in some cases only feeding one plant. It is therefore important to know which plant species are important for all wild bees.

Many other insects also visit plants such as hoverflies, flies and beetles but as they only carry small amounts of pollen they are contributing little to pollination.

Which plants are best

A good way to determine what bees like is to steal their pollen and identify which plants it came from. Observing the bees whilst they are foraging is also useful as then the extent to which they use plants for collecting nectar or pollen can be determined. This is exactly what Tom Wood did for his PhD, and as the studies were conducted on farmland he was able to identify the key farmland plants. This was the first time that this had been done for solitary bees on farmland.

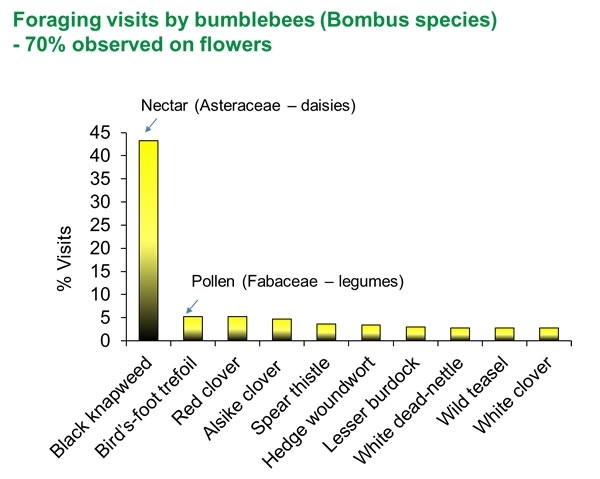

Figure 1 shows the top ten plants for bumblebee foraging. This includes several legumes which is why the first agri-environment options designed to encourage bees were primarily comprised of legumes.

Figure 1. Top ten plants for bumblebees on farmland.

For more details see Wood et al., 2015. Biological Conservation

There are now many different commercially available, legume based mixes comprised of various clovers, bird’s foot trefoil, sainfoin, and vetches. Having a range of different clovers (Alsike, crimson, red and white) can help extending the flowering period, as can cutting part of the area to delay flowering. Such mixes are best sown without grasses as they can quickly dominate. These areas can also be used to improve soil fertility and control annual weeds before establishing wildbird seed mixtures.

Where half of plot cut to delay flowering

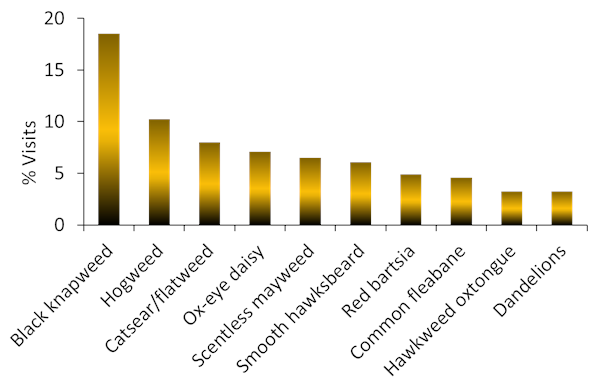

For the solitary bees, with the exception of knapweed, a different range of plants were preferred to bumblebees (Figure 2). Overall the key message is that the mixes typically sown on farmland will encourage more of the common bumblebees, but if we want to increase bee diversity then we should be aiming to achieve a great a diversity as possible of annual and perennial plants.

Figure 2. Top ten plants for solitary bees on farmland.

For more details on the foraging preferences of solitary bees see Wood et al., 2016. Biodiversity and Conservation.

Establishing wildflower mixes

These wildflower habitats can be sometimes difficult to establish, especially on fertile farmland so here are a few useful tips.

- First of all choose your site carefully. Very fertile soils at the bottoms of slopes are more likely to encourage grasses than herbaceous plants so these are best avoided, as are places containing noxious, invasive weeds such as sterile broom, couch and creeping thistle. If only fertile soils are available then chicory is an option. Select a sunny spots and avoid shaded areas.

- Wider the better, narrow strips are more quickly invaded by other plants so blocks of habitat are ideal.

- Before deciding on a mix it is always useful to have a look at similar habitats in your locality and see which plant species seem to do well, that way more chance of them being able to compete with grasses. I would avoid including any aggressive grasses in the mix such as Cocksfoot and Yorkshire fog, stick to fine grasses if at all.

- Many herbaceous species do better on less fertile soils so try to deplete soil fertility to start with by cropping without fertilising. Have a fallow period beforehand and keep cultivating to reduce the weed burden, the longer the better.

- Tailor the seed mix to the soil type and fertility, or use green hay from a local site. For better soils, species such as black knapweed, oxeye daisy, meadow cranesbill, yarrow, hogweed, vetch and chicory are more likely to persist. These will attract not only bumblebees but also solitary bees and hoverflies.

- Create a fine seedbed, broadcast the seed and then roll. Sowing can be done in the spring once the soil warms up (Mid-March to May) or early autumn (August to September). Mid-summer is avoided as the plants may suffer from higher temperatures and drought!!

- Once the wildflower mix comes through keeping topping (every 6 weeks or so) to reduce grasses, if done frequently there is less need to remove the cuttings. In the following years they should be topped annually, and any cuttings removed. This is very important as others the dead vegetation will encourage grasses and increase soil fertility. Time cutting so it is after the main flowering period (Mid-August under current Stewardship rules) or graze in the autumn.

- If grasses start to dominate there are various options (but note stewardship rules!) such as spraying with Fusilade. Poaching the ground can help keep the sward open but of course take care if thistles are nearby. Bees do like thistles though! Scarifying the ground can have similar benefits as found in SAFFIE project. This was done using a power harrow power harrow to 2.5cm in early spring when ground was fit to travel on (March). Consider including yellow rattle which parasitizes the grasses, but seed is expensive and it generally does better if there is also autumn poaching.

Good luck and be patient, it may take several years for some species to appear.

Other ways of providing flowers

The hedge base and rough grassland can also support many flowering plants. Unfortunately, some hedgerows do appear to be lacking in plant diversity after years of herbicide and fertiliser drift. Grasses, nettles and brambles appear to be the order of the day. These have their own merits but if we want to restore plant diversity then these areas need protecting from agrochemical inputs.

Pollinating insects not only feed on herbaceous plants, but also the flowers of trees and shrubs. It therefore helps to have a hedge cutting regime that allows shrubs to flower in hedgerows, many flower on second year wood. Establishing woodland and managing woodland to allow more light to penetrate will also help rejuvenate the ground vegetation. The British Beekeepers Association have produced a worthwhile leaflet on “Trees useful to Bees” that gives flowering times and whether they are a good source of pollen or nectar.

Finally, please don’t be too tidy, patches of weeds can often support early flowering plants such a red and white dead nettle which are important for early foraging queen bees (Lye et al., 2009).

References (all GWCT publications)

Holland, J. M., Smith, B.M., Storkey, J., Lutman, P. J. W., Aebischer, N.J. (2015) Managing habitats on English farmland for insect pollinator conservation. Biological Conservation 182, 215-222.

Lye, G.C., Park, K.J., Osborne, J.L., Holland, J.M. & Goulson, D. (2009) Assessing the value of Rural Stewardship schemes in providing foraging resources and nesting habitat for bumblebee queens (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Biological Conservation 142, 2023-2032.

Wood, T.L., Holland, J.M., Hughes, W.O.H. and Goulson, D. A (2015b) Targeted agri-environment schemes significantly improve the population size of common farmland bumblebee species. Molecular Ecology 24, 1668-1680.

Wood, T.L., Holland, J.M., Goulson, D. A. (2016) Diet characterisation of solitary bees on farmland:dietary specialisation predicts rarity. Biodiversity and Conservation 25: 2655-2671.

Wood, T.L., Holland, J.M. and Goulson, D. A. (2017) Providing foraging resources for solitary bees on farmland: current schemes for pollinators benefit a limited suite of species. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54: 323-333.