By Mike Short, Senior Field Ecologist

By Mike Short, Senior Field Ecologist

Our fox-tagging work in the Avon Valley got underway just as the bitterly cold ‘Beast from the East’ hit towards the back-end of February, and it’s just drawn to a close amid one of the hottest, driest summers we’ve experienced for years. River meadows that were laden with snow, and then totally immersed in floodwater, are now bone-dry and sun-scorched.

Weather-wise, it’s been an atypical year, which we will consider carefully as we make sense of the tens of thousands of GPS-fixes that we’ve obtained from tagged-foxes this season. For instance, the extreme weather patterns will undoubtedly have affected the abundance and availability of field voles – a key prey item for foxes that occupy grassland habitats.

To recap, in 2016 and 2017 we studied an unmanaged fox population using GPS-collars in the Upper Avon Valley, just south of Salisbury. Our research revealed that foxes were living at surprisingly high densities and that small mammals, especially water voles and field voles, were the most important food resource.

Historically lapwing, redshank and snipe all bred on these meadows, but there have been no known nesting attempts for at least a decade: a decade in which local landowners were paid a lot of money through agri-environment schemes to provide better habitat for breeding waders.

Photo: In the Upper Avon Valley water voles are an important food resource for foxes. (Photo © Mike Short/GWCT)

Recently, I was poring over historical wader survey data for the upper valley, and was amazed to learn that in June 1990, 24 lapwings (including at least 8 juvenile birds) and 2 redshanks, were recorded on two wet meadows – totalling 18 ha – in the heart of our fox study area. In 2017, nine adult foxes that we tracked, plus several more that were untagged, occupied those same two river meadows during the nesting season.

They were clearly no threat to breeding waders, because there were none, but according to Natural England’s ‘MAGIC’ maps – a publicly accessible interactive mapping tool – Lapwing remain a priority species for Countryside Stewardship in this area. Unless local landowners can be persuaded to try and reduce fox densities and the risk of predation more generally, then there’s little hope of breeding Lapwing and Redshank ever making a recovery there.

Back to this year’s fieldwork. I’ve been GPS-tagging foxes on one of our Waders for Real project ‘hotspot’ sites lower down the valley, where lapwing and redshank still breed, but not very well. The landscape here is quite different – the floodplain is broader, the river wider, there are far fewer linear drainage ditches, and as we saw, the river meadows properly flood, and are subject to different management and grazing practices.

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to cull foxes overwinter, which left me to catch resident foxes that had survived or had moved in from neighbouring ground. The wet spring made it a really challenging field-season, mainly due to the difficulty of finding locations where I could securely anchor snares (which we use to live-catch foxes for tagging-purposes) coupled with unexpectedly high levels of non-target activity, especially otter and badger.

Prior to the unprecedented flooding in April, I tagged two adult males caught within a stone’s throw of several new wader-scrapes, dug to provide invertebrate-rich foraging areas for lapwing chicks through our Waders for Real project. At the time, we were excited to learn how those foxes might forage on river meadows that are usually occupied by breeding lapwing, and where manmade micro-habitats were created to improve chick-survival. Alas, perhaps due to the flooding, both foxes left the area, one settling on mixed farmland several miles west of the valley, and the other on drier meadows where waders no longer breed.

After a forced break from snaring, perseverance paid off. In late-April and early May, I tagged two more dog foxes and two vixens, both of whom were lactating when caught. Annoyingly, the £2000 GPS-tag on one vixen – the 27th fox that I’ve tagged in the valley – failed after only 3 days, which left me a little irate to say the least, but fortunately I managed to recapture her and fit her with a new collar.

An advantage of using snares is that foxes cannot learn to avoid them. To say this feisty little vixen was unhappy to see me for a second time, would be an understatement: she did her very best to sink her sharp teeth into my hands, before grabbing hold of a piece of foam pipe insulation that I gave her as a distraction.

Fig 2. GPS tagging is revealing how foxes use river valley habitats. When handling foxes, we offer them something soft to bite on, which helps to occupy them whilst the collar is being fitted. (Photo © Mike Short/GWCT)

Tagging foxes is helping us answer a great raft of important questions concerning their management. As we move into an age of enlightened thinking on conservation, there is greater acceptance that breeding wader populations will only recover if we also address the impact of predators. It’s essential that we understand which methods work best: lethal or non-lethal control methods. For the latter, we’re particularly interested to know how fox movements are influenced by natural and artificial barriers, like rivers and electrified-fencing. Permanent mains-powered electric-fences are used successfully to deter foxes and badgers from entering reserves managed for wildlife, but how effective are temporary electric-fences used to protect vulnerable birds in the wider countryside?

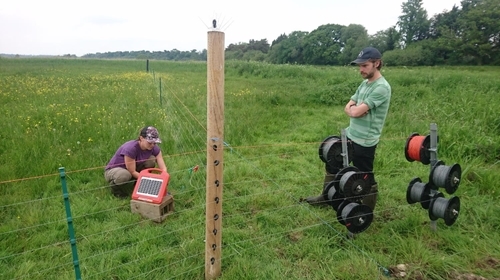

Fortunately for us, several pairs of lapwing nested in fields occupied by tagged-foxes, and two separate nesting areas were subsequently ‘protected’ with 8-strand electrified-fences, energised by a solar-charged battery. Temporary electric fencing is commonly used on arable farmland to protect lapwing and stone curlew nesting on fallow plots, and it’s been trialled on upland pastures where curlew still breed. But is it fox-proof?

Fig 3. Temporary electric-fencing is commonly used to try and protect breeding waders from foxes. In the Avon Valley, the GWCT’s wader monitoring team is trialling an 8-strand fencing design across multiple sites, but how effective is it? (Photo © Mike Short/GWCT)

The accuracy of the GPS-fixes we receive is largely determined by the availability of satellites when the fix is taken. Prior field-testing of our collars suggests that for ‘active’ fixes. i.e. those taken when the fox is moving, fixes are typically accurate to within ten metres, but usually less than five. The very clever technology we’re using also enables us to create ‘geofences’ within their territories, such that we receive mobile phone texts when a GPS-location marks the fox inside a geofenced area.

We created a geofence around the largest electric-fenced area, which encircled a short sward approximately 150m x 100m in size. We don’t think there was any substantial loss of power due to the circuit shorting-out on grass growing around the wire, yet one tagged-fox was recorded inside the protected area on several occasions, once, at least 50 metres inside the fence. We also found fresh fox scat inside the protected area, and camera traps facing inwards from corner straining posts recorded untagged foxes, and an otter inside the fence. Our sample size is small, but clearly, despite the careful thought that went into its design, this electric-fencing arrangement isn’t predator-proof. Next year, we plan to do more research on foxes and electric-fences and will use an alarm device which sends a text message should the fence's voltage ever drop too low or if the circuit is broken.

In case you’re wondering, the lapwing nest inside the geofenced area failed due to predation… but not by a fox or otter. A very experienced member of our Wader Monitoring team attributed its loss to either a Corvid, or a gull, which serves as a timely reminder that electric-fences will never protect vulnerable wader eggs from avian nest predators.

All the foxes that I tagged this season have now been relieved of their collars. It still amazes me that we can simply send the collar a message to drop off the fox, using a mobile phone… but that’s how the technology works… most of the time!

Follow the Waders for Real project

Visit the Waders For Real website and get all the latest project updates on Twitter and Facebook.

Support our wader recovery project