Key findings

- Female sparrowhawks were the most commonly seen raptor attacking or feeding on grey partridges.

- Grey partridges were not important in the diet of buzzards.

- The impact of raptor predation is highest at low grey partridge densities (below five pairs per 100 hectares).

- Many more grey partridges were shot in Sussex than were predated by raptors.

- The most important time for raptor predation of grey partridges was late winter.

- Losses to raptors can be reduced by providing tall cover in February and March.

The work to identify the causes of the decline of the grey partridge, begun by Professor Sir Richard Southwood's work on Lord Rank's estate in the 1960s, and followed by Dick Potts' pioneering study in Sussex in the 1970s. These were done when raptors were either absent or scarce.

Now grey partridges are at very low density with considerable gaps in their distribution, whereas lowland raptors, especially sparrowhawks and buzzards, are generally widespread and relatively common. In the late 1990s, our monitoring in the Sussex study area revealed a coincidence of raptor sightings with areas where grey partridges had declined the most (Review of 1999). Although seeing lots of raptors does not necessarily mean that they were eating the grey partridges, there was suggestive evidence that required urgent investigation.

Key questions

-

Which raptors eat grey partridges?

-

What proportion do they eat?

-

When does predation occur?

-

Does this reduce the population enough to cause decline?

-

If it is enough to cause decline, what can be done about it?

The project started by investigating raptor kill rates and the causes of local extinctions on downland in Sussex. It then developed into a study across 20 sites that contained different densities of raptors and partridges, spread across eight counties from Dorset to Lincolnshire. The aim was to gather information about partridge survival and habitat use from radio-tracking under different levels of raptor predation risk. We spent over 3,149 hours gathering data across 20 sites during the winters of 2000/01, 2001/02 and 2002/03.

Which predators were important?

Female sparrowhawks were the raptors seen most often attacking or feeding on grey partridges. Although buzzards were numerous at some sites, the data showed that grey partridges were unimportant in their diet, so it was unlikely that this species could be responsible for a large direct mortality of partridges. Peregrines and hen harriers both attacked grey partridges and were occasionally successful, but they were seen very infrequently.

When does predation occur?

Regular searches for partridge carcasses showed that most losses of grey partridges to raptors were in late winter. This was confirmed by an intensive study of sparrowhawk and buzzard diet in the breeding season conducted by Simon Smart, an MSc student at Reading University, who found the remains of a grey partridge only once in 73 prey items from five buzzard nests and 295 prey items from five sparrowhawk nests.

Further, the collection date of partridge carcasses predated by raptors and sent in by gamekeepers for post-mortem examination showed a peak of losses in February and March. Clearly, late winter was the most important time for raptor predation.

How many partridges do raptors eat?

Two separate sources of data gave closely matching estimates of over-winter losses to raptors. The first was from autumn counts in Sussex, taking into account subsequent losses to shooting. The kill rate by raptors based on carcass searches and adjusted for fox scavenging suggested that 12% of the partridges counted in autumn were killed by raptors. The second data source was from radio-tagging 181 birds across 20 sites.

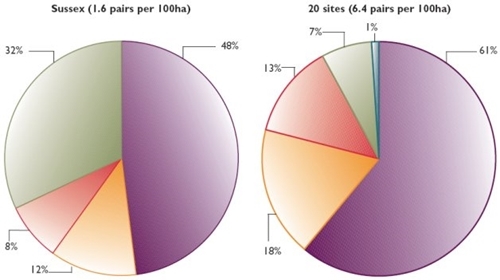

This suggested that losses to raptors over winter amounted to 18% when adjusted for fox scavenging. For comparison, shooting losses were 32% in Sussex in 1999/2000 (since 2000, reduced to under 13% - see Review of 2001) and 7% across the 20 sites in 2000-2003 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The pattern of over-winter losses of grey partridges in Sussex 1999/2002 (left) and 20 other sites 2000-2003 (right)

Are losses to raptors enough to cause partridge decline?

Computer modelling suggested that, at low densities, this level of loss to raptors would result in a 39% reduction in average spring pair density over the long term. Because shooting losses occurred before the peak time for losses to raptors, the two causes of loss were largely additive. Shooting alone at 40% resulted in a 23% reduction over the long term in spring stocks, and shooting and raptors combined reduced spring stocks by 52%.

Crucially, the impact of raptor predation was greatest at low partridge density; above approximately five pairs per 100 hectares the impact was much less. The density in Sussex was 1.6 pairs per 100 hectares, and averaged 6.4 pairs per 100 hectares for the radio-tagged birds in the 20-site study.

Manipulating habitat and shooting

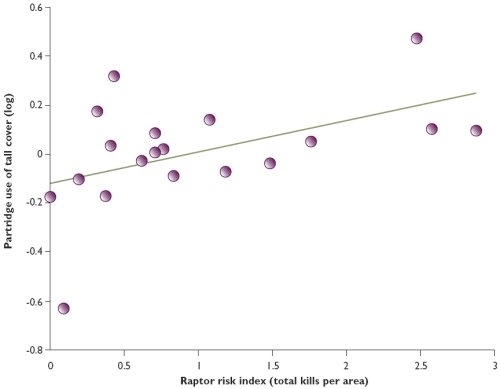

The habitat preferences of radio-tagged grey partridges showed that they used taller cover more when the risk of predation was greater (see Figure 2). Putting this together with the timing of peak losses of partridges to raptors, this means that to mitigate the impact of raptors, partridges need tall cover in February and March. Current practice is often to plough up cover crops at the end of the shooting season, ready for re-sowing in the spring.

The implication is that it would be much better either to leave such cover until the end of March, or to sow biennial crops that maintain cover throughout late winter and spring. There are also clear advantages to boosting partridge density by enhancing nesting and brood-rearing cover, thus bringing their density above the threshold of vulnerability to raptor predation.

Figure 2: Partridges use tall cover when risk of predation by raptors is high

Note: The raptor predation risk index was calculated as the kill rate of birds including grey partridges at each of the 20 sites.

Declining species will have low tolerance to shooting if the population mechanism that compensates for shooting losses is disrupted. In the grey partridge, reduced productivity has had this effect, and over-shooting can extinguish the stock. Banning shooting is not a solution, as the decline would continue so long as its underlying causes were not addressed. These causes are changes to farming that have taken place in the last 50 years.

The Curry Report and its proposal for farm subsidy to be directed partly towards conservation offers real hope. The resulting Entry Level Stewardship due to start in 2005 contains many features pioneered by the Trust, such as conservation headlands and beetle banks. It will be truly nationwide as, to receive the £30 per hectare subsidy, farmers will have to implement conservation measures from a large and flexible menu of options.

To save the grey partridge, it is important that landowners, farmers and shoot managers take full advantage of the opportunities offered by Entry Level Stewardship. At the same time, they must avoid shooting any remaining wild stock of grey partridges, not least by taking special precautions during driven red-legged partridge and pheasant shoots. Our leaflet Conserving the Grey Partridge gives details of these and other conservation measures to help the species.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful for generous funding provided by Game Conservancy USA. More than 100 farmers and keepers helped with the study in very many ways - sincere thanks to all of them.

Further reading

- Watson, M., Aebischer, N.J., & Cresswell, W. 2007. Vigilance and fitness in grey partridges Perdix perdix: the effects of group size and foraging-vigilance trade-offs on predation mortality. Journal of Animal Ecology, 76: 211-221.

- Watson, M., Aebischer, N.J., Potts, G.R., & Ewald, J.A. 2007. The relative effects of raptor predation and shooting on overwinter mortality of grey partridges in the United Kingdom. Journal of Applied Ecology, 44: 972-982.