By Mike Swan, GWCT Head of Education

Lets start by noting the words Predation Control rather than predator. In managing game and wildlife, how many predators you kill is of no great relevance; rather it is the predation that you prevent that matters. As a consequence, shooting odd random predators is of no great moment; what is needed is an integrated plan that addresses all the main issues for the species that we wish to protect.

Nesting wild pheasants, for example, can loose eggs and chicks to birds like crows, magpies, rooks, jackdaws and jays, as well as mammals like rats, stoats, weasels, mink and foxes. All these mammals can kill hens on the nest too, and foxes will take adult birds at any time of year.

Just picking a single species to control, or even the two or three which you judge to be most important, is not likely to have that much effect. If you suppress these, other generalist predators are likely to take up much of the slack, resulting in a much more modest impact that you would hope. The RSPB has found this out at Otmoor in Oxforshire.

Having carried out great habitat works to restore the site for breeding waders, and especially lapwings, predation became a big issue. Electric fencing to keep out ground predators allowed more lapwings to hatch, but the resulting bonanza of chicks attracted red kites, which carried off a significant part of the benefit.

What are You Trying to Do?

So, first things first. Before you set off at the predators, what are you trying to achieve? My little shoot is about producing enough wild pheasants for me to organise a few days rough shooting for seven or eight guns, without getting tangled up in a release programme. Others will be running a grouse moor or partridge manor where all the game is wild, while most lowland shoots will be looking to encourage wild production of pheasants and/or redlegs, as well as releasing extras each autumn to guarantee their shooting. In each case the optimum strategy is slightly different, so, for example, those who are releasing game will have an extra late summer focus on preventing predation of naive poults who have no parents to teach them the ropes.

Sustainable control

“We sorted the foxes when we took over the shoot two years ago”. How often I have heard something like that when I have asked about predation control in my role as a GWCT game management advisor. Such ideas show a fundamental lack of understanding of how predation control works. Nature abhors a vacuum, so whatever temporary reduction in predator numbers you achieve, new colonists will fill the space, usually quite quickly. However, this does not imply failure; rather the temporary reduction takes the predation pressure off, and if this is at a critical time, it can make the world of difference.

So, the keeper who is ‘at the foxes’ around release time can reduce poult losses significantly, making a big difference to the percentage return at the end of the season. Similarly, someone who takes predation control seriously during the nesting season can dramatically increase the productivity of wild game, through reducing the numbers of eggs and chicks lost, as well as protecting sitting hens. In both cases, this effort will need to be made every year at the critical time.

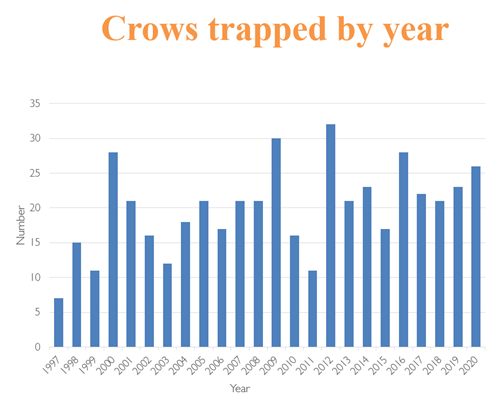

In most cases the keeper will find that the numbers of the various predators killed are roughly similar year on year. In my own case, for example, my annual ‘bag’ of crows has averaged between 20 and 21 for the last 25 years. There have been quite wide variations, but if you look at the bar chart below, I’m sure you will agree that there is no sign of long-term change. What this shows is that my control is entirely sustainable, with the crows bouncing back each year. I am simply taking an annual ‘crop’ of crows to enhance my crop of game, while also helping a significant suite of other wildlife too.

Subsidised predators

Anyone who wonders whether it is acceptable to do this ought to ponder something else too, and that is subsidised predators. The example of ravens and tortoises in the Mojave Desert of California may seem very distant, but it is very relevant. Over the last few decades the Californian raven population has grown enormously, ‘subsidised’ by all sorts of foods provided by people, such as roadkill, and scavenge from landfill sites, sewage works, and intensive livestock farming. Ravens have probably always taken the odd young tortoise, but all these extra birds have caused a massive increase in predation pressure across the Mohave, driving a steep population decline.

Here in the UK, the way we manage our very crowded countryside means we provide a similar support system that maintains artificially high populations of foxes, corvids and probably others like rats too. So, not only is sustainable control of these species perfectly justified, for game management reasons, you might also argue that we have a responsibility to be trying to redress the balance for other vulnerable wildlife. Its interesting, is it not, that gamekeepers are doing their best to deliver this service at no cost to the public purse, but right now the new General Licences for both England and Wales are making that much more difficult.

What the Science Tells Us

Back in the 1980s the GWCT carried out a piece of ground breaking research into the impact of predation control by a gamekeeper on the partridges of Salisbury plain. The keeper concerned, Malcolm Brockless, was simply asked to do his best to deal with the legally controllable predators using the normal tools – traps, snares, rifle and shotgun.

What this showed was that after just three seasons there were four times as many wild greys on the experimental area compared with a similar patch 4km away. The treatments were then switched, and three years later the autumn count on the new keepered area was just short of four times that of the original patch.

Controlled experiments like this are very expensive to carry out. You need to fund the keeper, in this case for seven years, but then there is all the scientific monitoring too. So, it is hardly surprising that there are not many such studies. The GWCT’s Upland Predation Experiment of the early 2000s was even more ambitious, and gave similar dramatic results for the likes of curlew, lapwing and golden plover, as well as grouse, blackgame and grey partridges.

What these experiments show us is that a well planned predation control programme can be very effective. They also show that you need to address a suite of predators to have much effect. Being hard on foxes alone may well make a lot of difference to survival of released pheasants and redlegs, but if you want to help wild production, you need to cast the net wider. Most of the common predators have catholic tastes, making use of a wide range of prey, so if you address just one or a few species, the rest will be likely to take advantage of at least some of what you produce.

So, if you want to do a reasonably good job, ask yourself what is at risk and when, and target your efforts accordingly. For most shoots, this means a spring campaign to protect nesting birds. It should start before the breeding season, and target foxes, rats, stoats, weasels and corvids. So, that is likely to include use of fox snares, tunnel traps, Larsen traps and corvid cages, as well as night shooting of foxes. Anything less is a relatively weak attempt, and while it may help, it will not reap maximum benefit, either for your game, or other vulnerable wildlife.

Do not forget the mink

Lest anyone wonders, mink are another predator to consider. If you have water on the shoot, chances are feral American mink are visitors to your patch. They can be responsible for murderous mass kills in release pens, and will take nesting game and wildfowl, not to mention other ground nesting birds. The answer is to run a few GWCT mink rafts, to detect their presence, and then trap them quickly.

This blog first appeared as an article in Shooting Times.