Written by Kathy Fletcher, Phil Warren, Felix Meister and Henrietta Appleton

What the grouse counts tell us about this season’s prospects

In July and August, GWCT staff and their pointing dogs revisited study sites across the North of England and Scotland to count red grouse. After the pair counts in the spring, which aim to determine the number of breeding pairs, these brood counts in July aim to estimate the breeding success. The current monitoring regime extends over 21 sites in England and 24 sites in Scotland. As many of the study sites have been monitored since the 1980s, this GWCT dataset is one of a kind and offers crucial insights into red grouse population dynamics.

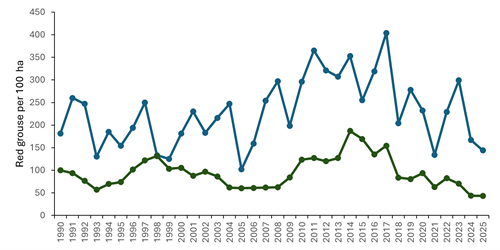

From this year’s spring counts, we know that pre-breeding densities were much lower than last year (40% lower in England and 34% lower in Scotland). The latest brood counts recorded further losses of adults (36% in England and 29% in Scotland). However, the remaining adult birds did produce more young when compared to last year, with an average young-to-old ratio of 1.4 in England (0.9 in 2024) and 1.3 in Scotland (0.6 in 2024). This combination of adult losses and improved breeding success meant that the average post-breeding density was lower in England than last year and similar in Scotland (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Annual post-breeding density of grouse. Blue = England, Green = Scotland

The regional break down (Table 1) shows improved breeding success compared to last year across all regions in Scotland, but there are differences within England. The average breeding success was lower in Southern Dales compared to last year, but higher in the Northern Dales. This is likely to be influenced by the severe heather beetle damage that was evident at all count sites in the Southern Dales and North York Moors, but which effected fewer count sites in the Northern Dales.

|

Region

|

2024

|

2025

|

|

England:

|

|

|

|

Southern Dales

|

1.5

|

1.0

|

|

North York Moors

|

1.0

|

1.0

|

|

Northern Dales

|

0.7

|

1.7

|

|

Scotland:

|

|

Borders, Perthshire, Angus

|

0.7

|

1.4

|

|

Dee & Donside

|

0.7

|

1.3

|

|

Highland

|

0.4

|

1.1

|

|

Moray & Nairn

|

0.4

|

1.5

|

Table 1: Regional mean productivity values (young-to-old ratio, where 1 = same number of young and adult birds), comparing 2024 with 2025

For many estates in England and Scotland, 2025 will act as a building year, where grouse populations are allowed to recover from the catastrophic crash of 2024. The exact reasons for the recent dramatic fluctuations in grouse numbers continue to be poorly understood. GWCT is currently undertaking two major research projects designed to shed light on these drivers: the Maternal Grouse Project involves comprehensive monitoring of grouse hens through the breeding season, and the Long-Term Grouse Count Analysis involves a detailed statistical analysis of our long-term datasets, such as decades of pair count and brood count data.

Why are grouse prospects so important?

The prospects for the forthcoming season are important from many perspectives. If there is a harvestable surplus then the beaters, flankers, pickers up, loaders and gun bus drivers have employment for another season and the hotels, caterers, gun shops and other local businesses benefit from the money spent by the guns – and the wages of the up to 100 people involved in a typical shooting day. The significance of this should not be overlooked in some of the remote rural areas that grouse shooting occupies; it is estimated that grouse moor tourism contributes at least £100million to the economy[1].

Other benefits of the investment year in year out in the management of our heather moorlands (whether shooting happens or not) include the conservation of globally and nationally protected species such as heather, curlew, merlin, lapwing and black grouse; the mitigation of wildfire risk through vegetation management and therefore the protection of vital carbon stores; the retention of water on the hill and natural flood management; restoring peatlands through blocking grips/rewetting; the maintenance of a landscape that is valued by the millions who visit upland designated landscapes; and, importantly in rural areas, the social benefits of bringing people together given the isolated nature of many rural occupations.

But these economic, environmental and social benefits are under threat across the UK from increasing legislative pressure and the incentivisation of alternative land uses and economic models such as commercial forestry and rewilding.

With muirburn in Scotland coming under tighter regulatory control[2] and in England, restrictions to burning practices proposed through the expansion of licensing for burning on deep peat[3], prescribed burning is increasingly being relegated to a management tool of last resort. This is worrying as it risks frustrating the achievement of many of the benefits outlined above, both directly, and indirectly through having a negative impact on red grouse numbers.

Reducing opportunities to manage vegetation would increase wildfire risk, for example, thereby undermining efforts to protect peatlands and conserve upland biodiversity (including the direct loss of wildlife from slower moving species to eggs in nests) – all brought into sharp focus by the recent devastating fires in the Peak District and Morayshire. We have also pointed out that there is no evidence that the existing regulations have been effective in reducing carbon emissions – the single focus of the regulatory changes.

The need for informed, evidence-based decision-making has never been greater. Encouragingly, this point was echoed by cross-party MPs at the Westminster Hall debate on 30th June, where many cited GWCT science in defence of driven grouse shooting and its wider conservation value.

Given this need, the GWCT is launching a major new research project, in partnership with The Heather Trust, to quantify the ecosystem services delivered by traditional moorland management and model how these might change under different government policies and climatic scenarios. It will focus on key ecosystem services such as biodiversity, reducing the risk of wildfire and tick-borne diseases, and mitigating and adapting to climate change. This will support previous work that has identified the role played in wildlife conservation by predation management as undertaken on grouse moors and the consequences for ground nesting species if grouse shooting ceases[4]. The project will be vital in demonstrating the role of sustainable grouse moor management in meeting governments’ ambitions and targets in these areas. It will also position traditional moorland management within emerging natural capital markets, reinforcing its value to policymakers and investors alike.

At the same time, the Trust is unlocking the potential of its unparalleled long-term data sets by analysing decades of spring and summer grouse counts across the English and Scottish uplands. This will help identify broader drivers of red grouse decline, such as climate change, weather, disease, habitat quality and changes in management, and their relative importance as factors driving population change.

On the practical side, our practitioner evidence programme is helping estates across Scotland and northern England document and demonstrate responsible moorland management, particularly in relation to emerging regulatory requirements. Alongside this, our advisory services continue to provide tailored guidance on habitat management, predation control, biodiversity delivery, and other natural capital services. As a result, we are delighted to announce that Leah Cloonan will be leading the development of our Grouse Technical Services offering in the north of England.

The GWCT could not do this research, advisory and policy work without the generous support of landowners, land managers and our members in both funding our work and in providing research sites.

[1] Recent estimates are: BASC £100m; Moorland Association £121m England alone.

[2] Muirburn will require a licence from 1st January 2026 under the Wildlife Management and Muirburn (Scotland) Act 2024. Provisions for muirburn licensing remain to be concluded with a revised Muirburn Code due this Autumn.

[3] Defra is proposing the expansion of the Heather and Grass etc. Burning (England) Regulations 2021 to all Less Favoured Areas and the redefinition of deep peat at 30cm. The revised Heather & Grass Burning Code is to become a broader vegetation management code,