By Chris Heward, Wetlands Research Assistant

By Chris Heward, Wetlands Research Assistant

In the ten years between 2003 and 2013, Britain’s breeding woodcock population declined by 29%. That’s a worrying statistic and corroborates the 50% decline in breeding range over the last 40 years, documented by the British Trust for Ornithology’s (BTO) Atlases, which led to the woodcock’s conservation status being upgraded from ‘amber’ to ‘red-listed’ in December 2015.

The population decline was measured by a collaborative national survey conducted by the GWCT and BTO, enlisting the help of hundreds of volunteers to survey woodland sites across Britain for breeding woodcock. The first survey, in 2003, estimated the national population to be in the order of 78,000 ‘pairs’. Just ten years later, a repeat survey produced an estimate of 55,000 ‘pairs’.

Each winter, about one to one and a half million woodcock arrive here from Scandinavia, Finland, the Baltic States and Russia and available evidence suggests that these large continental populations are stable. This is in stark contrast to the UK’s small resident breeding population, to which the red-list status specifically refers.

But why, given the relative health of woodcock populations across most of Northern Europe, is our British population declining so severely? Beginning to answer this complex question will be one of the key aims of my PhD thesis.

The national survey data show that woodcock have not declined evenly across Britain – some populations, particularly those in the south and west, have been harder hit. I am investigating the causes of the declines by looking at the common characteristics of sites where woodcock have declined most markedly.

This work is ongoing, but I have already found that woodcock tend to have been lost from woods that are smaller and more isolated and that sites where thriving woodcock populations remain are often those dominated by coniferous woodland and birch, although it is likely that these two points are linked to some degree.

My PhD also involves collecting first-hand data in the field to tell us about the behaviour of woodcock on an individual basis. To do this I am catching and radio-tagging woodcock and following their movements over the breeding season.

This behaviour has rarely been studied in the past and what little is known about the woodcock’s breeding ecology originates from GWCT studies conducted in the late 1970s and 1980s. By repeating this work, 30 years on, I am hoping to see how woodcock have responded to recent changes in woodland habitats.

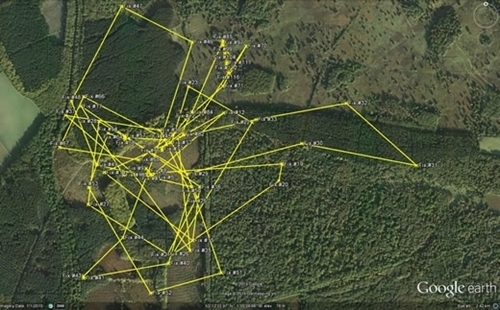

Most exciting are the new avenues of research made possible by advancements in tracking technology. This summer, I am using tiny GPS loggers to monitor the movements of male woodcock during their roding displays. This work is important for two reasons.

Firstly, most of what we currently know about our breeding population – such as estimates of its size and trend – are based on the results of the GWCT-BTO surveys; and these use counts of roding males to assess abundance.

By gaining a better understanding of these displays, particularly the frequency of roding behaviour and the size of each bird’s roding ground, we can refine our population estimates and interpret the survey results more accurately.

Secondly, understanding which specific habitat features are used by woodcock during the day and when roding should help us provide advice on woodland management and improve woods to better suit the species’ needs.

Whilst roding, male woodcock are looking to locate receptive females, who watch from the ground; and they probably rely on clearings and rides over which they can perform their displays. The use of GPS loggers will help us understand the importance of these woodland features and the necessity of active woodland management to maintain them.

Outside of the GWCT, this work is co-supervised by Dr. Andrew MacColl of the University of Nottingham. The Breeding Woodcock Survey is a collaborative programme with the British Trust for Ornithology and my fieldwork in Nottinghamshire has been greatly aided by the Birklands Ringing Group. I am grateful to the private landowners and the Forestry Commission who have provided access to their land.