Minotaur beetle

Occasionally in summer and autumn I can be found in sunny pastures on my hands and knees besides a cow pat, clutching a bottle of vodka and brandishing a tent peg.

Occasionally in summer and autumn I can be found in sunny pastures on my hands and knees besides a cow pat, clutching a bottle of vodka and brandishing a tent peg.

To the puzzled observer, you can offer only one explanation that won’t get you sectioned, and that is: “I am surveying dung beetles.”

Be it cow, horse, dog, pig, human, sheep or any other terrestrial vertebrate dung – there will be a dining community of beetles, flies, worms, fungi and bacteria to suit. The dung is found within minutes of being deposited, then it is colonised, eaten, bred in, carried away or broken down into the soil in a matter of days or weeks. This waste processing and removal is a vital part of the Earth’s nutrient cycle, where the exchange of materials and energy never ends. That’s not all dung beetles do – they are an important part of the food chain; they help to aerate soil through their burrowing; they remove herbivore gut parasites – the list is long.

We have about 6,000 species of dung beetle in the world, many of which go about their lives unnoticed within the dung or underneath it. However, I bet you can all picture the large African dung beetle rolling its disproportionately huge dung ball across the savannah by the light of the Milky Way. And we’ve all heard of its close relative, the sacred scarab (Scarabaeus sacer), which inspired amulets, seals and jewellery of the Ancient Egyptians – yes, this was a dung beetle too!

Closer to home, many of our 60 British species of dung beetle are members of the same Scarabaeidae family, but we also have a fascinating group called the Geotrupidae, the earth borers.

These are large, shiny black beetles that sometimes exceed an inch long, often with beautiful metallic green or blue hues. True to their name, they bore deep into the earth under areas of dung, to create feeding and breeding burrows. If you look carefully at the edge of a day-old cowpat you might see a little spoil heap, and next to it a tunnel opening slightly smaller than a penny. To identify the occupant, you can stick a peg or wire down the hole and dig around it with a trowel, until you excavate the beetle. It is quite easy to learn the different species because most of them can be identified with a field guide and hand lens, but occasionally they need to be taken away for microscopic identification, hence the use of vodka for preservative. Sorry to disappoint those who assumed it was there to get me through during a day of poo-sifting!

Of our earth-boring species, the minotaur beetle (Typhaeus typhoeus) is particularly fascinating. Most commonly seen in autumn when the adults emerge, it is our only UK dung-roller, but not quite on the scale of the aforementioned African beetles – we are talking rabbit droppings!

Minotaur beetles have certainly earned their classification as earth borers. Once they have fed enough and are in mating condition, a pair will choose a spot near to a rabbit latrine and proceed to dig a tunnel up to a metre and a half below the ground. Both sexes have strong front legs adapted for digging; nevertheless, a tremendous feat for a 2cm critter! Perhaps they go to this depth seeking consistency in temperature and moisture.

The rabbit (and sometimes deer or sheep) pellet is rolled across the ground and down the burrow to provision a series of side-chambers. When the weather is mild in winter or spring, the female minotaur beetle lays an egg in each chamber. The larvae hatch and eat their own pellets of dung, much like diners in restaurant booths – an orderly strategy adopted by many dung beetles. The male protects the nest burrow using his large projecting horns, which the beetle was named for. The adults die in spring or summer after their brood is established, whilst the larvae pupate and emerge the following autumn to start their own search for a mate and epic burrow construction.

Like many other dung beetles, they fly about searching for mates and food at night and can be attracted by light. The further north in the country you go the rarer they are, and they are largely restricted to short turf over light and sandy soils. Perhaps one day I will get lucky and come across a burrow with a big spoil heap near a rabbit latrine. I would love to meet one in person too, though I may need a longer tent peg (and possibly a JCB).

Jess Brooks

Advisory

Photo credit: Trevor and Dilys Pendleton

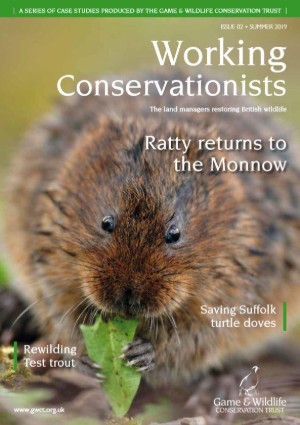

Our second issue of Working Conservationists, this 40-page A4-size colour publication features eight case studies produced by the GWCT, focusing on the land managers who are helping to save British wildlife.

Buy Now - £3.95 >

eBook - Buy Now - £1.99 >