Key points

- Burning patches of heather in a rotation is commonly used for moorland management, especially when managing for red grouse.

- This study used aerial photographs and fieldwork to look at the long-term effect of rotational burning on moorland vegetation.

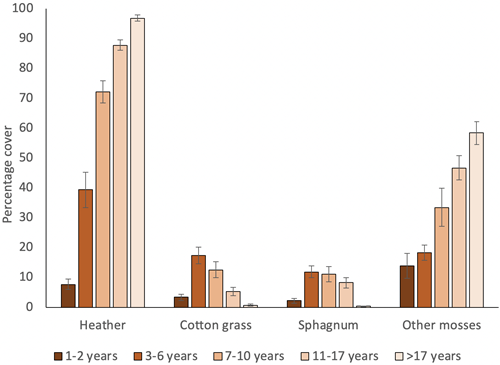

- Heather cover dropped after a burn, and gradually rose to almost complete ground cover on areas burnt more than 17 years before.

- The highest levels of sphagnum moss and cotton grass were found on areas burnt between three and ten years previously, and were very low more than 17 years after a burn.

- This paper supports other studies which find the highest cover of sphagnum mosses within ten years of rotational burning.

Background

Burning is a commonly used tool to manage the vegetation on heather moorland, especially but not exclusively where it is managed for red grouse. It is used to stop heather growing too tall and woody, and, after the burn, heather regenerates to give new growth, which is considered to be more nutritious and palatable for grouse to eat. Heather burning for this purpose is performed in a cycle, with different patches burnt each year in winter, with the aim being a quick, cool burn that does not affect the peat underneath. It gives a patchwork of different height areas for grouse and other wildlife.

Burning is a commonly used tool to manage the vegetation on heather moorland, especially but not exclusively where it is managed for red grouse. It is used to stop heather growing too tall and woody, and, after the burn, heather regenerates to give new growth, which is considered to be more nutritious and palatable for grouse to eat. Heather burning for this purpose is performed in a cycle, with different patches burnt each year in winter, with the aim being a quick, cool burn that does not affect the peat underneath. It gives a patchwork of different height areas for grouse and other wildlife.

Rotational burning has been a traditional management tool for centuries, but recently it has been the subject of much debate, with concern that it can be environmentally harmful, especially when it is done on blanket bog. Some studies have found evidence that heather burning promotes heather growth, at the expense of other plant species. But a long-term study carried out at the Moor House National Nature Reserve in the North Pennines, running from 1954, showed that carrying out prescribed burning on a ten-year rotation increased the cover of peat-building species like sphagnum moss and cotton grass. Sites with longer burning cycles had more heather and fewer species that are thought of as peat-building (all plants can build peat, but some do so more quickly than others).

Because this study at Moor House has given so much information about the impact of heather burning, much of what we know in the field is based on its findings. It is important to look at other sites to see whether the findings apply more widely. This study looks at the effect of heather burning on vegetation at different times after burning on another moorland site in the Pennines, to test the finding from the Moor House experiment on a site that is actively managed as a grouse moor.

What they did

This study looked at moorland which is managed for red grouse and has significant areas of blanket bog. We examined how the vegetation responded after different time intervals since burning.

This study looked at moorland which is managed for red grouse and has significant areas of blanket bog. We examined how the vegetation responded after different time intervals since burning.

It is possible to estimate the time since a burn using aerial photographs, so the scientists compared photographs from different dates to identify which parts of the moor had been burnt during what time period. The scientists used aerial images from December 2001, September 2007 and September 2011 to classify areas burnt before December 2001 (more than 17 years ago), between December 2001 and September 2007 (11-17 years ago), or between October 2007 and September 2011 (7-10 years ago). Ten separate burns within each of these age categories were studied.

For areas that had been burnt since the last aerial photos were taken (i.e. after September 2011), the scientists visited the sites to estimate burn age. Signs such as black, charred heather stems and freshly cut fire breaks showed that an area had been burnt one to two years earlier, whereas signs such as grey-silver charred stems, early heather regrowth and other plants growing back showed that a burn was three to six years earlier.

The vegetation growing at each of the 50 burn plots was carefully surveyed, taking a series of measurements of overall vegetation height, and percentage cover for each of the main plant species present. This was carried out 20 times within each of the 50 burn sites. In total, the scientists carried out 1,000 vegetation surveys.

These results were combined with the information on how long it had been since each site was burned, and the scientists analysed the effect of burning on the vegetation.

What they found

The amount of cover of each plant species was affected by how long it had been since the area was burned, but different species groups showed different response patterns:

Heather

Heather cover was lowest in the plots that had been burned most recently, gradually increasing in cover over time.

Sphagnum mosses

Cover of sphagnum mosses was low after a burn, increased to be highest in the categories burnt 3-6 and 7-10 years ago, before levelling and declining in the older burns. There were more species of sphagnum moss in the years 3-17 since a burn, but in the first two years and more than 17 years since a burn the number of sphagnum species was lower.

Other mosses

These mosses showed a similar pattern to heather: low in the areas burnt most recently, and gradually rising as the burn was longer ago.

Cotton grasses

Cover for cotton grasses was low straight after the burn, then rose in the 3-6 and 7-10 year categories and dropped off again in 11-17 to be very low in the 17+ year categories.

What does this mean?

These results are similar to what was found at Moor House, where areas of moorland in a longer burn rotation shifted towards a predominantly heather plant community. This study found those areas that had not been burnt for more than 17 years had the highest proportion of heather and the lowest sphagnum mosses.

Also in line with the Moor House findings, the amount of peat-forming sphagnum mosses and cotton grass were highest in the age categories covering three to ten years since a controlled burn had been carried out.

Other papers have recommended that to maintain plant biodiversity on moorland, rotational burning or cutting should be carried out when the heather reaches 25cm in height, and that if it is allowed to reach 40cm, most other species will be lost and would then have to regenerate from the seed bank or recolonise from other areas after burning or cutting.

This study represents the findings at only one site, and it was not possible to consider unburnt areas for reference. It adds to our knowledge in the field, and supports the findings at nearby Moor House, but more research is needed to understand the subject more fully and at a wider range of sites. This study does suggest that in the shorter term after rotational burning, it is the peat-forming species that benefit.

Read the original abstract

Whitehead, S.C., & Baines, D. (2018). Moorland vegetation responses following prescribed burning on blanket peat. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 27: 658-664.