Newts

Not many animals enjoy a saturated countryside, but for amphibians this will do nicely. Right now, across the country, newts are emerging from their winter snugs to a waterlogged world, and can begin swaggering towards their ponds to breed (the expression ‘pissed as a newt’ comes from the funny gait).

Not many animals enjoy a saturated countryside, but for amphibians this will do nicely. Right now, across the country, newts are emerging from their winter snugs to a waterlogged world, and can begin swaggering towards their ponds to breed (the expression ‘pissed as a newt’ comes from the funny gait).

Our three species of newts – smooth (Lissotriton vulgaris), palmate (Lissotriton helveticus) and great crested (Triturus cristatus) – have relatively similar lifecycles and requirements, and are widespread in distribution. The great crested newt is slightly pickier with its habitat and therefore the least common of the three. This species and its habitats have strict legal protection because the UK’s population is very important in an international context. Requirements to survey them and mitigate impacts mean they are much maligned by developers and responsible for huge and expensive hold-ups to significant infrastructure projects across the country, in some cases costing five figures per newt!

Smooth newts and palmate newts are very similar – around 10cm in length and predominantly brown, with a black-spotted, orangey-yellow belly. In the breeding season, male smooth newts develop a big wavy crest, and male palmates can be distinguished by their comical fat webbed hind feet. Males appear quite blotchy with dark spots on their upper bodies and crests. Females are difficult to identify unless in the hand: the spots on the underside of a smooth newt will extend to the tip of the chin, whereas palmates have a plain chin (smooth: spotty, palmate: plain!). Great crested newts are a different beast altogether, reaching over 15cm with black, warty skin, and a bright orange underside with thick black spots. Spot patterns are unique to each newt, much like our fingerprints. The males develop the huge black jagged crest that gives the species its name.

Mature newts actually only spend about a third of their lives in ponds, and this will usually be between February and July. Most of their time outside the spring and summer breeding season is spent laying up under stones, woodpiles, mud or thick thatches of vegetation. A good pond will have lots of this type of sheltering habitat nearby, so that the newts don’t have to travel far between their terrestrial and aquatic homes, which can be risky. Lots of animals like to eat newts: herons, foxes, hedgehogs, snakes, kingfishers and cats are the usual predators.

Rather than spewing out their eggs in a big mass like frogs and toads, newts are more discreet. A gravid (pregnant) female likes to lay her eggs on thin, rounded leaves like water mint and speedwell. When she senses a leaf of the right consistency, she manoeuvres herself onto it and deposits a single egg. Then she folds the leaf over it with her back legs, sealing the egg inside. Great crested newt eggs are about 5mm in size with a creamy yellow yolk, whilst smooth and palmate eggs have a duller whitish yolk and are smaller overall. Despite this careful parcelling strategy, their eggs are often preyed on by fish, big insect larvae and sometimes other amphibians, so a single newt will laboriously lay and wrap 200-400 eggs in a season.

Rather than spewing out their eggs in a big mass like frogs and toads, newts are more discreet. A gravid (pregnant) female likes to lay her eggs on thin, rounded leaves like water mint and speedwell. When she senses a leaf of the right consistency, she manoeuvres herself onto it and deposits a single egg. Then she folds the leaf over it with her back legs, sealing the egg inside. Great crested newt eggs are about 5mm in size with a creamy yellow yolk, whilst smooth and palmate eggs have a duller whitish yolk and are smaller overall. Despite this careful parcelling strategy, their eggs are often preyed on by fish, big insect larvae and sometimes other amphibians, so a single newt will laboriously lay and wrap 200-400 eggs in a season.

Newt larvae develop feathery gills and, unlike frogs, they grow their front legs before their back legs. At ten weeks old they can breathe air and become known as ‘efts’. By the end of the summer, most efts will have left the pond to find terrestrial dens of their own.

Newts have quite an ambitious attitude to food, and will try to eat any living thing they can fit in their mouth. They have a sticky tongue to capture prey such as mites, spiders, worms, shrimps, nymphs, hoglice and leeches, and they will shake snails out of their shells. Their eyes are too big for their bellies at times. Some observers have reported seeing newts struggling to spit out earthworms and slugs that they simply cannot swallow, and this is made more difficult by their blunt ‘vomerine’ teeth, which were designed to grip prey as they shake and swallow.

Inundated with slugs as I am, this spring I am hoping to attract newts and frogs to my new garden pond, and I would encourage anyone to create a little pond if they have space, because it benefits all sorts of wildlife.

I have several amusing memories involving newts, but perhaps the most self-deprecating was my first ever night as a trainee consultant ecologist on a pond survey. Our job was to carefully pan the torchlight along the water looking for newt activity, and I thought a grassy island a little way out into the pond would be a great vantage point, so I jumped on it. But, alas, it was a cunningly disguised duck raft, which shot along the surface of the pond as I plunged underwater. The good news was that we found a newt egg in the watermint stuck to my hair afterwards…

Jess Brooks

Advisory

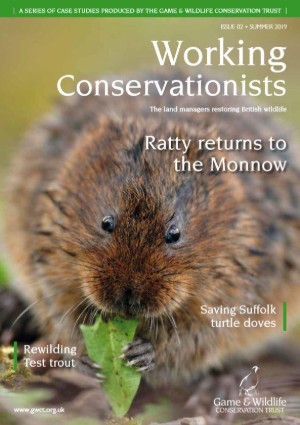

Our second issue of Working Conservationists, this 40-page A4-size colour publication features eight case studies produced by the GWCT, focusing on the land managers who are helping to save British wildlife.

Buy Now - £3.95 >

eBook - Buy Now - £1.99 >