Contents

An animal of the open country

The brown hare’s origins in the British countryside are obscure, but palaeontology suggests that it was not in our native fauna at the end of the ice age while the land bridge to the continent was connected. At that time our hares were mountain hares, a species now largely confined to the highlands of Scotland. The brown hare did not appear until the Roman times or perhaps a little earlier (2,000 years ago), by which time much of the lowlands were already being farmed. It is even possible that the Romans introduced hares, for sport-coursing was a popular form of hare hunting in Roman Gaul at this time.

Hares like the open country, and in western Europe arable farmland is their natural habitat. Originally they evolved on the grassland steppe of central Asia and spread west as early Neolithic man cleared the primeval deciduous forest.

Hares are mainly nocturnal animals moving over wide areas to graze on young grasses, cereals and herbs. They feed at night and mainly rest during the day while they digest the previous night’s forage.

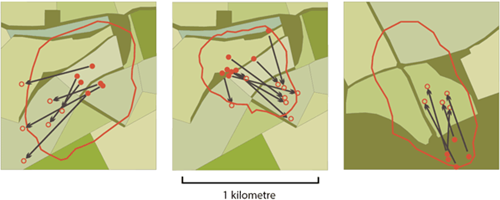

The ecology of hares on open farmland. Three hares on a Hampshire farm showing the core

areas of their home ranges (red line) and some typical daily movements between daytime

resting areas (solid red circles) and night-time grazing area (open red circles). The dark green

habitat represents woodland and other colours arable and grass fields. Hares often use

nearby woodland for daytime shelter in winter.

Living in the open, hares are potentially exposed to predators like foxes. To protect themselves they depend on cryptic colouration and remaining still - often in shallow depressions (or ‘forms’) in the ground. Hares have huge eyes and ears and can usually detect predators long before they are seen themselves. Hares rely on running fast to put distance between themselves and danger.

The hare’s changing fortunes

Hares can be prolific breeders and may become pregnant as early as February. A female can produce three or even four litters of three or more leverets a year until September. At birth the female leaves her young together in the open but over the following days they move apart so they are usually found singly. After sunset the female returns to their birth place and suckles them for a few minutes. One visit per day is all the youngsters get from birth until they are fully weaned.

The hares’ breeding success is partially dependent on the summer weather. Warm, dry springs and summers allow females to have successive pregnancies and leverets survive well. Under wet and cold conditions, breeding success is poor and leverets succumb to cold and diseases such as Coccidiosis.

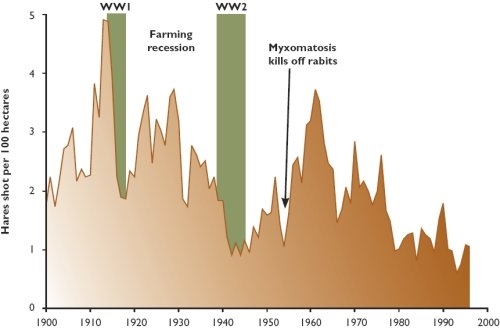

Bag records of hares from an average of 12 England lowland estates from 1900 to 1996.

Old estate game books show that in Victorian and Edwardian times many more hares were being shot each year than has been the case in recent years. This bag record directly reflects hare abundance and we can conclude that hares are now far less abundant than they were three generations ago.

There are at least two important factors that have caused this reduction. Firstly, many predators are now more abundant than they were a century ago and, secondly, modern agriculture is less suited to hares than traditional farming was.

The main predator of the brown hare is the fox. Although foxes perhaps only rarely surprise and kill adult hares, they can systematically prey on and kill leverets to such an extent that a fox family can eat the entire production of the local hare population. However, modern farming could make hares more prone to fox predation than traditional ley farming did.