Background

- Worked across six farms close to Llanilar, near Aberystwyth.

- These farms comprise an organic sheep and beef farm and conventional livestock farms with a range of agriculturally improved and unimproved pastures.

- A few fields use beet fodder as part of the farm rotation prior to reseeding.

- The total area is approximately 448 ha encompassing 110 fields.

- These farms offer migrant woodcock suitable nearby daytime cover to rest in and adjacent pastures for night-time feeding through the winter.

- Woodcock numbers have been counted and birds ringed across these farms for the last 12 years.

The study examined the relationships between woodcock feeding sites and soil quality, followed by an assessment of the feasibility of using counts of woodcock in winter to engage and guide farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

The study examined the relationships between woodcock feeding sites and soil quality, followed by an assessment of the feasibility of using counts of woodcock in winter to engage and guide farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

With heightened focus on improving soil health to maximise carbon uptake and maintain agricultural yields, indicator species are being increasingly used as a preliminary marker of habitat quality. We aim to trial the use of woodcock counts in winter as an indicator for farmers of fields where action may be required through altered practices to improve soil quality. We will examine the relationships between woodcock feeding sites, soil invertebrate abundance and physical soil characteristics and assess the feasibility of using counts of woodcock as a proxy for soil quality in lieu of more expensive and time-consuming measures of soil attributes and soil fauna.

Initial findings

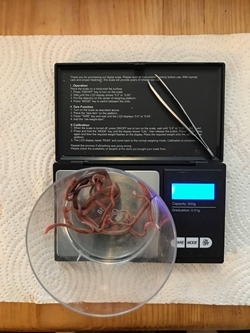

The study used thermal imaging to plot woodcock on fields to establish areas of ‘high use’ and areas of ‘low use’ and then compared soil variables between these areas.

The study used thermal imaging to plot woodcock on fields to establish areas of ‘high use’ and areas of ‘low use’ and then compared soil variables between these areas.

Preliminary analysis of the data found a slight bias of woodcock use towards areas with higher invertebrate numbers and overall weight, however this was less marked than expected. When investigating data for soil organic matter (SOM) it was found that overall there was a stronger positive correlation between woodcock use and SOM than that found in the invertebrate data.

The soil variable showing the strongest correlation with woodcock use of pastures was stone burden. Much of the soil in the study area was very shallow (10-15cm), and in uncultivated old pasture the stone burden lay at the base of the sample. However, on fields that had been cultivated in recent years, ploughing had disturbed the stone burden and distributed it throughout the soil column. The data suggest that this was a significant deterrence to woodcock feeding on these fields. As invertebrate numbers didn’t always negatively correlate with stone burden, it seems fair to conclude that the physical difficulty of probing in stony soil was the reason for woodcock avoiding these areas. There is also little doubt that high levels of stone in soils also constitutes a physical barrier to root penetration and prevents good drainage, which are vital to good soil health.

This study was limited by delays in funding due to Covid resulting in a rush to complete the fieldwork before woodcock left on their spring migration. The number of soil samples had to be limited to fit the timescale, but despite this the scoping study has served to highlight the importance of good soil management, particularly in areas with thin soils such as many parts of West Wales.

Livestock pastures in areas like West Wales are an important wintering habitat for a significant proportion of our UK migrant population of woodcock. It is clear that careful management of soils in these areas will ensure that this continues to the be the case and will bring the added benefits of higher biodiversity and greater carbon capture at the same time as improving pasture yields. This throws into question the rush to plant trees on farmland, particularly when recently published science suggests that the pasture soils have a higher capacity to store carbon than those of woodland.